I will take any excuse to go back and re-watch Westworld. Today, after reading something by another filmmaker, Arthur Woo, I went back and looked through what at first appears to be a very simple scene in season one: Bernard Lowe (Jeffrey Wright) and Dolores Abernathy (Evan Rachel Wood) having a conversation. However, with Westworld, deceptively simple things are often more complex.

Here are my thoughts on how the camera placement and movement reinforces and expresses the narrative in this scene. In other words, how the camera’s visual storytelling works with the actors and the screenplay. Production design, blocking, sound design, lighting, and lots of other factors are important, but I’m just concentrating on this for now.

Westworld EP104: Dolores and Bernard opening scene. Running time 3 minutes.

Starting with a reflection of Bernard in Dolores’ eye, the camera pulls back to reveal her face, at eye-level. Dolores describes being trapped in a dream. Cut to wide shot showing both characters inside a glass room. They are literally trapped in a physical space that itself is a visual conflict; the glass makes it appear open, but it is actually closed. Bernard is standing, pacing a little. Dolores is seated, still.

Starting on Dolores at eye level with the camera—and therefore with the viewer—establishes/reinforces that this is Dolores’ scene and it is told from her dramatic point of view (although it’s not necessarily her literal POV). Bernard is guiding her in finding the truth of her existence. He provides the conflict through a series of questions and orders, but every decision in the scene—every decision that moves the story forwards—is hers.

As Dolores describes her dream and the murder of her parents, Bernard gives an order: “Limit your emotional affect, please.” The camera crosses the line of action at this point. Reality has changed. The camera switches to an objective, profile view of Dolores, putting the viewer outside her as she states, “Everyone I cared about is gone. And it hurts…”

Bernard offers to make the feelings of pain and sadness go away, seeing them as a result of her programming. “Why would I want that?” asks Dolores. The camera is facing her again, allowing us to identify with her. And we are below her eye-level, emphasizing the importance of her decision: to keep her emotions. “The pain. Their loss. It’s all I have left of them.”

At its core, Westworld is a story about the nature of consciousness and sentience. What is it that defines us as living beings? As self-aware? Sentient? This scene touches on a theme which continues throughout the series, across seasons: the philosophical idea that we are the stories we tell ourselves. Dolores’ story is initially a result of programming; she is programmed to re-enact a complex storyline on a repeated cycle. In this scene, we see that change.

For the show’s creators (Lisa Joy and Jonathan Nolan), Dolores’ story—and therefore her sentience—might be as valid as that of the humans, despite the fact that her story, the story she believes, was originally written for her by others. This is partly because it develops and branches away from the initial narrative she was given. Dolores goes on to talk about this. “I feel spaces opening up inside of me. Like a building with rooms I’ve never explored.” She is becoming self-aware by adding to her own narrative.

Cut to a three-quarter profile of Bernard’s reaction. Before he speaks, we see he is stunned by her words. He tries to dismiss them, “That’s very pretty… Dolores…” He questions the origin of her assertion. The camera becomes looser. There’s almost a hand-held feeling. We aren’t as certain any more. Dolores asks, “Is there something wrong with these thoughts I’m having?”

The camera crosses the line a second time, to outside the glass room. We see the invisible trap, but this time it’s from Dolores’ side, looking towards Bernard, pushing in as he sits down. “No. But I’m not the only one making these decisions.” This is new information. Bernard is not fully in charge or in control. The visual shows he is trapped too.

Again, the camera crosses the line, switching to the other side of the action. “Can you help me?” asks Dolores. “What is it that you want?” asks Bernard. “I don’t know. But I think there may be something wrong with this world.” Camera is now in an objective profile again. We are observing Dolores, instead of identifying with her at this point. It encourages us to think, “What does she know? What does she guess?” Cut to Bernard’s reaction. He thinks he knows what she means. Cut back to high angle extreme close up on Dolores; we are looking into her mind as she reflects on her self: “Either that or there’s something wrong with me. I may be losing my mind.”

Camera comes back to a two-shot, this time inside the room, same side of the action, from Dolores’ side looking towards Bernard. Camera moves down, indicating what’s coming is increasingly important. Bernard cleans his glasses, symbolically finding a fresh way to look at things. Cut to close up of Bernard, on same angle, slightly to one side as this is also an objective view; it is not his scene. Although we see both eyes, so his reaction is important.

“There’s something I’d like you to try. It’s a game. Called The Maze.” Cut to close up, almost straight on, low angle, on Dolores, with looking space to the right as she looks to Bernard: “What kind of game is it?” Bernard describes the maze. “If you can do that, maybe you can be free.” At this point Bernard is framed in an off-axis, tight close up, from slightly below his eye-line, indicating power.

Cut to camera pushing in to tighter and tighter shot of Dolores’ face. She considers. “I think… I think I want to be free.” She has made her choice and the shot on her now matches the close up on Bernard. The camera is also below her eye-line, indicating that she has made a powerful decision which will drive the story forwards. Dolores and Bernard finish the scene as equals, visually and narratively.

Category Archives: Film making

Simon’s Last Train

“Who are we going to throw off the bridge?”

Simon Ricketts and I were meeting at the Lower Red Lion in St Albans to discuss Last Train. This was a short film he and fellow Watford Observer (WO) reporter Lionel Birnie had written under the name of Goober Scripts. They’d asked me to produce and direct, so I’d maxed out my credit card buying film stock and food while borrowing a 16mm camera from the BBC Film Club.

In return, I’d asked that the Goobers help out with logistics. Simon was now the 1st Assistant Director and our climactic scene involved a stuntman falling from a railway bridge. I’d found an experienced stunt coordinator with a huge inflatable bag designed for high falls. Perfect. Problem was, Malcolm the stunt man had hurt his back, so we needed a stand in.

Simon sipped his second Guinness. “Well,” he confided, “I did used to do a spot of rock climbing. But I gave it up a few years back when I had a fall. Not far but lost me nerve. Never got the courage to go back up.” “This bridge shouldn’t be that high,” I reassured him.

“Maybe,” he paused to imbibe dark courage through froth. “If no-one else is game, I’ll do it.”

The bridge we’d chosen was over a footpath which used to be a single-track railway in Harpenden. It was maybe 25 feet up, which doesn’t sound that much when you say it. Nevertheless, seeing is not saying. Once Simon was in the actor’s wardrobe and Christine the makeup artist had given his cheek a dark bruise, he didn’t look too keen. “I’m not sure about this, Keith. Maybe Gavin should do it?” Gavin, our lead actor, peered over the parapet. “Er, I don’t think I can,” he told us and scurried off.

Simon watched him go, looked back at me and inhaled. “It’s me then.”He climbed over the edge, feet precarious on four centimeters of crusty cement lip sticking out below. Jason, our other actor, hung on to him from behind as I ran down to the path below. Simon looked out, straight ahead to the dark horizon. “Make it quick!”

“Action!”

Jason let him go and, arms flailing like a gravity-defying Wile Coyote, our erstwhile screenwriter threw himself off the bridge. All for a story he’d created, which he felt he needed to tell. Ploompf! The airbag caught him, perfectly on target. “Cut!”And Simon emerged from the giant cushion’s canvas embrace to enthusiastic applause.

“That was fantastic!” he said, “You should have a go. Honest, it’s really fun! Although I have ripped Gavin’s trousers. Do you need another take?”

Mended trousers, two more takes. “Wave your arms around some more!” and Simon really did seem into it. One more jump for our stills photographer, Pete Stevens, also from the WO. Pete whirred off shots then “It’s a wrap!” Last Train’s cast and crew gathered to celebrate with a glass of Champagne. “So the bridge thing was okay after all?” I asked Simon. “Nahhhh. To be honest, Keith, I was talking a load of cobblers. Mostly for myself. It was bloody terrifying!”

But he’d done it anyway.

That’s how I’ll remember you, Simon. Last Train and you did it anyway. I hope that last journey was peaceful. I miss you, my friend.

————-

Photo: Simon and Lionel confer over a storyboard on The Car, their second Goober Scripts collaboration. Photo credit: Pete Stevens/Creative Empathy

Note: I’d originally titled this piece “Jump, you fucker, Jump!” after the Peter Cooke/Dudley Moore “Derek and Clive” sketch. Then realized the reference will be missed by most

Content Theft

We got an email today from an astroturfing (look it up) “charity” called Creative America. Creative America (funded by the studios and unions) wants to expand the movement for intellectual property security. That sounds like a good thing, right? Right?? Wrong.

When distributors regularly take producers’ works and make profits from those works but don’t pay the creative talent a realistic return because they allegedly spent all the money on distribution and marketing, that’s content theft. When Instagram asserts that it “does not claim ownership” of your pictures but claims a “fully paid and royalty-free, transferable, sub-licensable, worldwide license”, that’s content theft. When a studio takes taxpayer money (incentives) to produce a film but avoids paying taxes on a billion-dollar grossing movie by creating subsidiaries to hide the income, that’s another kind of theft. Maybe content theft should be the name given to the RIAA campaign to deprive recording artists of residuals from radio airplay. That one was pretty blatant theft because it’s not standard practice in most other countries. Or is content theft what happens when Disney perverts the law intended to encourage creativity by having the copyright term extended to life plus 75 years?

None of these things help me, the creative monkey who dances when someone pays the organ grinder. The only thing which helps me is when producers, distributors and/or studios or clients invest in NEW work and pay a realistic amount for that. That doesn’t mean bullshit tentpole sequel movies with overpriced stars and under-written scripts. Uwe Boll is the poster child for movies that fail despite big names, big marketing and being created on the backs of related successful franchises. That model doesn’t work. What actually works is new movies that the public can afford to see without add-on price-hyping gimmicks like 3D or IMAX, without outdated distribution methods and “windows”, and with realistic marketing and marketing budgets based on realistic expectations of the actual value of the intellectual property. New good work where everyone working gets paid at a realistic, reasonable rate.

And take that further, new work where everyone involved shares in the success through residuals. New work is the only thing which helps me. None of the posturing. None of the criminalizing. Not SOPA. Not PIPA. Not threats of 35 years of imprisonment which is what these companies demanded for Aaron Swartz, the co-creator of RSS who committed suicide this weekend after being hounded with legal threats generated by the interests of these parasites. None of that helps. Just bookings for work where the profits are shared equitably with the participants instead of siphoned off by a few at the top. That’s what helps me.

So, yes. Content theft. A red herring to fuck up the creative world of the internet. Where studios don’t have to produce a damn thing, just keep milking the money cow and attacking creativity in the world where the rest of us live. This attitude has become pervasive. Distributors and agents are demanding releases for images of property that is so far out of copyright it’s a joke (eg. European castles). Yet this protectionism only works in one direction. Getty Images pissed photographers off royally this week by freely giving pictures to Google for them to sublicense without attribution or recompense. Hollywood has enough money to employ shills but not to actually make movies without taxpayer handouts (aka incentives) while avoiding actually paying tax back into the system. It’s fucking remarkable.

How the did copyright law become this screwed up by companies that don’t actually pay fucking income tax? This nonsense has been tried since movies first began, with Edison and his compatriots seeking to monopolise the film industry through use of patents a century ago. Trying to control access didn’t work then and won’t work now. Independent artists, distributors and exhibitors have always been extremely important in the world of the arts but now we have threats of life incarceration for copying publicly available documents—not secrets, but academic journals; work in the public domain. Meanwhile bankers and CEOs blatantly destroy jobs, create homelessness, steal pensions and launder money for terrorists. Terrorists, you know, people who actually fucking blow other people to bits, shoot our troops, kill and maim for their cause—banks can help fund those guys and there are no consequences because something like “HSBC is too big to jail” so is therefore outside the law? But distributing the results of publicly funded research—papers actually in the public domain—might be grounds for effectively ending an individual’s life?

Current intellectual property law is outdated and nonsensical. Academics are showing support for Mr Swartz by actively tweeting links to PDF’s of their journal articles. [http://gizmo.do/UZL8zZG]. Did you know that the only reason prints of Nosferatu still exist is because of piracy and subverting copyright? In the real world, Disney should never get to own your arm just because you got a tattoo of Mickey Mouse. In the real world, the rules should apply equally to the little guy and the big corporation. The so-called creative industry needs to get sensible about what makes art, instead of hoping art “just happens” like a natural bodily function in a world where we see identical bland sedans being burped out by every single car company on the planet. And Government needs to embrace its role in this with better access to information in the digital age instead of trying to kill the messenger (or finding some dubious sex charges to keep him locked up in Scandinavia).

The GOP had a wonderful opportunity for real IP reform during last year’s elections. Imagine, a real platform that Republicans could use with strong appeal to young voters and the tech-savvy Generations X, Y and Z. This was a platform they could have used to actually change and improve lives. Instead, the paid-for politicians retracted the Republican Study Committee Intellectual Property Brief [https://www.eff.org/document/rsc-report-three-myths-about-copyright-law], a report which would have simplified the legislation and actually encouraged creativity. And last month the GOP fired its author Derek Khanna.

Democrats are no better when it comes to embracing the potential of the internet and fair access to everything it can provide. Notwithstanding the attacks on investigative journalism through misuse of the Espionage Act of 1917, last year saw Obama’s Whitehouse demanding tougher federal penalties for suspected copyright infringement, including adding copyright to the list of serious crimes that can justify wiretapping in the expanded Patriot Act. Imagine, copyright is now as serious as blowing up a plane full of people. Unless you’re a banker.

Tough laws, harassment and life sentences for copying and distributing work, especially work in the public domain, is bullshit. If it didn’t work with the dismal failure of a war on drugs, how can it work in a war on access to artistic works? Obviously the old paradigm is dead in a world where everyone is connected, in the world of the internet. If a motion picture production company can’t make money within 10-20 years of creating a film, then chances are pretty high that it wasn’t commercially viable. You don’t need life plus 75 years to create a library of financial flops in the hopes of a long tail well after the author’s children are collecting pensions. And at the same time, we can clearly see that the Department of Justice doesn’t give a shit when an offender is rich, which just tells us that these so-called get-tough policies are really only about who is paying whom. The goal shouldn’t be to create bigger legal departments but to create art.

So, our message to Creative America is, no. No, you’re not. You’re not creative in any sense of the word other than creative lying, bullshit and ignorance. Get fucking real and we might have something to talk about. Right now, we don’t. Go back and read Derek Khanna’s RSC brief and start working towards that kind of system. You need to understand that copyright is a bargain between the public and the creators, trading some freedoms in return for more artistic works. Until you understand that copyright is ultimately about what benefits the public, first and foremost, you’re a bunch of astroturfing shills, riding the backs of truly creative people and doing nothing to help them.

——–

Updated Jan 4, 2018: because scribd.com have ironically used electronic protection to prevent downloading the text of Derek Khanna’s RSC brief. Nevertheless, the Electronic Frontier Foundation has made it accessible

Serious not serious

I was thinking I might start this series of Wisdom From Laura. However, I’m fairly bad at blogging lately (you might have noticed) so who knows how many I’ll do. Here’s the first.

We were talking about Nicolas Cage the other day and Laura mentioned about how he’s gone from this good actor who didn’t take himself too seriously to an actor who is serious about his craft but also, unfortunately, seems to take himself way too seriously. And that’s the insight:

Take your work seriously, but don’t take yourself too seriously.

I think I’ve been doing this for many years, just never saw it in those terms. I’m living the dream, man. Something like that, anyway.

Red Eye

Last week I worked on a short film, Raised Alone. We were shooting on the Red One and I was the gaffer, then stepped up to DP for three days while Rob, the original DP, went to look after his wife who had a baby during the shoot. I never usually have time to write up the experiences from what I’m doing, but here, for once, are some of the things I learned and some of the things I was reminded in the past week.

===

Learning #1: this was my first shoot with the Red One and, yes, it’s a wonderful camera but… it has some serious problems, including the awful cables which trip off the power or the others that cause annoying flickering in the viewfinder. Cutting off power seems trivial–just switch it back on. You would think that until you realize it takes 90 seconds to reboot the camera. We had as much downtime for batteries and flaky cables as I’ve had with film loading issues. Having said that the picture quality is lovely. I’m sure the post folks will be extremely happy.

Reminder #1: being prepared is the best thing in the world. Scouting locations, planning shots, storyboarding, rehearsals, etc, etc. However, experience can still trump all of that because, in the light of the (inevitable) unforeseen, you have to stay flexible while still achieving the vision.

Learning #2: if you want to use a big light to create moonlight, you really do need a crane or a cherry picker. Related to that is…

Learning #3: when you’re using a Fisher dolly and have enough risers, a 10-foot jib doesn’t add that much to your shoot. I suppose that’s unless you rig the jib on the dolly’s arm and then add your risers. Not a very stable idea, however.

Reminder #2: you can’t expect a crew to work 12 hours on a meal of sandwiches every day. Feed the crew and work smart. Tired and/or hungry people aren’t creative or as productive.

Reminder #3: get a good gaffer, a good sound dept and an AD who knows what they’re doing and, if you’re prepped, you can achieve some pretty amazing things with a truck full of gear and tight schedule.

Reminder #4: always try to get a few really difficult shots because challenge motivates the crew and if you pull them off, your footage will be a cut above the ordinary. However, don’t sacrifice coverage when time is tight.

Reminder #5: location managing is actually incredibly important on a low-budget shoot. If the person doing that job doesn’t get film-making, then you’re going to waste a lot of time finding nearby parking, accessing the location, running around for craft services and staging gear in impractical places.

Reminder #6: there’s often more light than you realize and prime lenses rock.

Reminder #7: a very large Cooke zoom can also rock but a trombone shot is going to take at least an hour to get right, especially with your 450lb dolly set on a slope.

Reminder #8: there’s no substitute for an extras casting specialist if you’re casting extras. Promises that lots of friends/family/colleagues will show up never pay off.

Learning #4: when shooting digital files, use time of day timecode. What a simple but brilliant idea. I love it.

So, there you have it. More important than any of the above, my crew in both grip and electric and in the camera dept were totally awesome, and the lead actors were great. The director was ambitious and well-prepared. I’m looking forward to the next one.

Filmmaking Focus

This is really simple. My focus from now on will be exclusively on creating moving pictures. That includes film development and production, all forms of digital video creation, editing, animation and compositing. It does not include film programming, film selection, teaching beyond a one-day specialized workshop or training outside on-the-job knowledge sharing.

There, I said it.

Video on the PSP 2000

So, I finally figured out, with a little help from the web and a lot of trial and error, how to get all my movies exported in a format that I can put on my new PSP. First off, you need to connect the PSP to your computer via a USB cable. Second, you need a Memory Stick Duo in your PSP. I put in a 4GB card, because I figure I can have all of my shorts and a ton of other stuff on there.

When the PSP is connected, the card appears as a drive/folder on my Mac. Add a folder called VIDEO at the top level. I added some sub-folders called SHORTS, DEMOS, TRAILERS and so on. The PSP recognised them all fine.

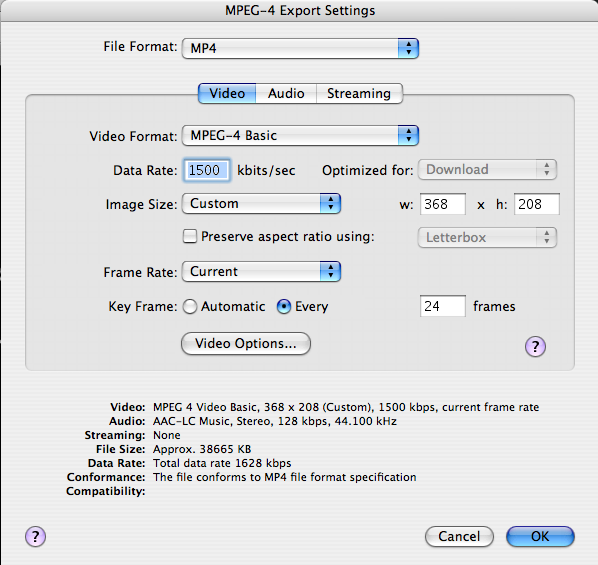

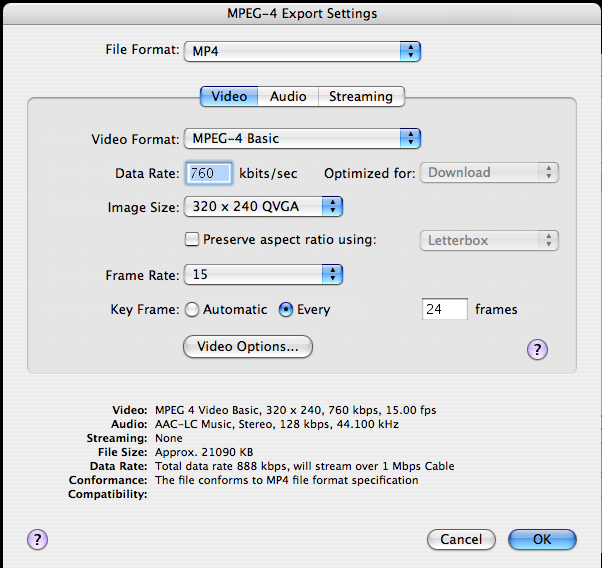

To get my videos in the right format, I used Quicktime Pro. Exporting as MP4, either MPEG-4 Basic or MPEG-4 Improved both seemed to work. Maximum size of 4×3 videos seems to be 320×240 on the PSP. Maximum size for 16×9 videos is apparently 368×208. I used the highest data rate, 1500 kbits/sec. Sound is AAC-LC, 128 kpbs, 44.1 kHz. Below are a couple of screen grabs of my export settings.

WIDESCREEN (16:9):

STANDARD (4:3):

Make sure the filename has the extension .mp4 (case doesn’t matter) and transfer to the VIDEO folder (and sub-folder, if you made one) on the PSP’s Memory Stick Duo.

And then the bit which nearly drove me crackers (Gromit); making a thumbnail image. It’s actually really bloody simple but nowhere in Sony’s documentation or anywhere online could I find it. Simply find an image (eg. export one out of Quicktime or do a screen grab) and make it the following dimensions (I used Photoshop): 160 x 120 pixels at 72 pixels/inch. Using Photoshop’s “Save for Web…” function, make sure it’s less than 8kb (so around medium resolution) and save a JPEG.

Give your thumbnail exactly the same name as your video file. For example, video.mp4 and video.jpg. Then simply put them both in the same VIDEO folder on the PSP. Voila! The PSP will create an additional weird “Corrupted Data” file when you look under the menu after disconnecting the computer/USB link. Delete this. You will then have just your nice video with a thumbnail. And it plays just fine. In fact, it looks really very very nice. Hurrah!

Editing: notes

These are my notes from the SXSW 2007 mini meeting on editing. [Personal comments and observations are in square brackets].

====

First off, it doesn’t really matter which format you shot on. It’s about story. [This comment from one of the editors on the panel].

David Lynch shot [parts of?] Inland Empire on a PD150.

Hardware: All brands of firewire drive have failures in a given 12 months. ATA drives are better. It’s really important to have back up drives and projects.

Directing: If you say everything is terrible, the editor will never go out on a limb and create something that’s never been seen before. Hopefully, you’re experimenting all the time.

Often a dialog scene will be too long; flexibility is needed. Reactions and body language can tell story as well as lines. You need different angles; coverage. A scene may not play in the context of the longer film. One shot masters don’t always work.

On set: Don’t just start shooting the close up at the point you think you’re going to cut in; actors can’t start at “intense” straightaway.

Fix small things first. Don’t edit from a place of panic.

The original Superman (and the new Casino Royale) reached a pinnacle of fast cutting. Also Don’t Look Now.

DD Allen [panellist]: Watch and learn about rhythmic editing, eg. Reds and The Limey, especially the conversations in the latter.

Label tapes correctly!

====

Casting: notes

These are my notes from the SXSW 2007 mini meeting on Casting. [Personal comments and observations are in square brackets].

====

Working with casting directors: First, you need to have a script. Then you need finances in place (sometimes a letter of intent is enough).

Casting directors work through word of mouth. Ten weeks notice is required at the very least to begin casting for a feature.

In casting a film, the casting director will have conversations with the director and will read the script. They will take pictures and resumes to the director. Also, it’s now usually the practice to upload auditions to the web.

Casting directors are there to direct the actors in the room and then the director has sessions with them. They are part of a collaboration between the director and the actors. They use standard and non-standard avenues, eg. agents and also schools, craigslist, etc. They are not the same as a casting facilitator.

A facilitator is an assistant who gets resumes, sets up auditions and the director makes decisions.

Great actors: come prepared, ready to work, are not too chatty but still very human. They make no excuses. They are people who really enjoy their work. They’re open, smart and can be given some direction.

Hire an LA casting director if you’re looking for name talent; it’s all about connections and relationships [note: this was from a professional casting director].

Jo [one of the panellists] almost always works with another casting director. They bring different things to the table.

Local. Local means no travel days, no per diem, hotel, etc. They have to have a local address and be able to show up on short notice.

Jo: “We do like smart actors.”

Lieblein: “Thinking actors are the coolest thing.”

Actors who haven’t watched the show are not wanted.

Kids: you’re also hiring the parent!

A good casting director should manage your expectations, which will depend on the quality of the script and the project.

You should have a plan, eg. five names and a set date for passes, then cast.

Directing Actors: notes

These are my notes from the SXSW 2007 Mini Meeting on Directing Actors. [My comments are in square brackets].

====

Share your vision and ideas [this applies to crew too]. Make the actors feel comfortable; they must trust you and feel safe. Let them know you’re a team and they’re respected.

The lead principals should have some sort of rehearsal. Often, there’s also a dinner [where they get to meet each other and the director without the pressure of being on set].

Talk about the feeling of the role and the line. Be supportive and introduce ideas. Be willing to be wrong and open to new ideas.

Set emotional objectives and know the emotion of the scene. 80% [of film acting] is tone, 20% is content (lines, dialog). The film is not about the lines. It’s about the reaction to the lines. Watch out for actors coming out of character in reactions [eg. waiting for their next cue].

Don’t be afraid to challenge actors. Professional actors want to be directed. Also recognize when they give you something good.

With non-professional talent: communicate in terms the actor knows and can relate to. You can fake reactions from non-actors (eg. Spielberg using characters in costume to get kid reactions in Close Encounters). However, you have to do this kind of thing with respect for the person and the actor.

Workshopping: a day in which to explore some emotions, in an honest way, without faking out actors on set. [Faking out actors on set destroys trust and undermines the whole process].

Casting directors: to find a casting director, you can look up the CSA website.

Shooting the entire scene from every angle (including close ups) helps the arc and intensity of performance.

Less is more. Be honest. And remember that, if environment didn’t matter, we’d all shoot green screen [all the time].

====

Recommended viewing: the two disc set of Dog Day Afternoon. Watch disc 2.